For many African Americans, tracing their family roots is challenging. That’s primarily due to slavery, frequent name changes, and limited records. For Black History Month, the Kukua Institute in downtown Pensacola hosted a genealogy workshop designed to give participants more tools for discovering their ancestors and telling their stories.

Support Local Stories. Donate Here.

The workshop, “Researching Your Family. Telling Your Story,” was organized by Robin Reshard, director of the Kukua Institute and also an award-winning local historian and storyteller. The workshop was divided into three distinct areas: genealogy basics, literature research, and storytelling methods.

“And all of that goes into how we pull people off the paper and make them this full human being with all these amazing experiences and stories,” said Reshard, noting searches shouldn’t only focus on when people were born and died, but also what happened during their lives.

This means telling the story between the truth, the facts, and what she calls, the spirit.

“Taking oral history, taking genealogical records, census data and so many other publicly available records and combining those with the oral stories that we hear from our parents, from our great grandparents, from our neighbors — the good, the bad, and the ugly — and really telling the full story of our human experience. So this was focused on the African American experience.”

Dr. John Veasley, a member and past vice president of the West Florida Genealogical Society, focused his presentation on the basics of genealogy. Like he did when launching his own research when his father died, he says to start building your pedigree chart with yourself, then learn what you can from older family members.

“I remember my most staunch supporter was my mother,” said Veasley. “I would ask, ‘Did you know this? Do you know this person? Do you know that person? Have you heard of this name? Of that name?’ And she could tell me stuff that helped me to better know what my results were, whether they made sense, whether these were actually people in the family that she knew.”

Family Bibles, obituaries, cemeteries, church records, census wills, and property records are good resources, along with birth, death, marriage, and military information. If they exist, many of those records are available on websites such as FamilySearch.

“You can set up your own family tree," Veasley added. "The way that they make you document it helps you be more accurate in what you're getting and what you're recording,” he said. And it's free; that's the good part.”

Today, people are sharing family information and photos on social media. DNA is another tool available in recent years. Through DNA, Veasley was able to trace his roots back to the Djola people living in Guinea-Bissau. But, he cautions to be prepared for surprises.

“When you do DNA testing, all those secrets that your family didn't tell you, they're going to be there,” he said, adding that it helped him to find other people he didn’t know about. “And we were able to connect, through our common ancestor being a great-grandfather, a great-great-grandfather. And through my ancestry, DNA, search, I have been able to locate so, so many family members on my mother's side and father's side.”

Still, most Black people in the United States can only trace their roots so far, before the trail goes cold.

“Yes, there are roadblocks, and the biggest roadblock is American slavery,” said Veasley, confirming that Blacks were not entered into census records, in general, until 1870. Prior to that, he estimated that free Blacks, who might appear in records by name, accounted for only about 11% of the entire Black population. “So, their information was recorded. I have been lucky finding Freedmen Bureau of Labor contracts that take me back to at least 1845.”

Other hurdles include erroneous data in the census and other records, particularly when it comes to peoples’ ages and names. Veasley has found at least eight different spellings of his own last name.

“But, you take the names that you find and the family members that are associated with that person so that you can make sure that you're talking the same person from census to census, and the years and dates of birth, those things,” he suggested. “Those will fluctuate because of the time of year the census is being taken and the person giving the information.”

Veasley advises taking the time to look at the actual enumeration record — not just the summary, and don’t trust any single source.

Beyond genealogy-specific tools, many other resources are available to take family research to the next level, according to award-winning public historian, Joe Vinson.

“Newspapers that have been digitized, lots of archives, and libraries that have digital collections,” Vinson began. “So one of the first places that I always look is newspapers.com. They have the Pensacola News and Pensacola Journal. Those are available for searching back to the 1800s.”

While newspapers are a great resource for finding people mentioned for doing something that might be newsworthy, there was a time when African Americans were largely left out of the narrative.

“The fact is that, you know, for many years, the Pensacola News and Pensacola Journal were not especially interested in reporting on Black Pensacola,” Vinson said. “So, there are newspapers that were specific to the Black community, The Colored Citizen, the Pensacola Voice. And those are available in certain archives, but they're not necessarily digitized yet. So researching those is a little bit trickier.”

Vinson says he learned that local information can be found outside the area while researching a man named Walker Thomas for the Pensacola News Journal’s obituary series, Righting the Past.

“He was a correspondent for Pensacola for national African American newspapers, the Indianapolis Freeman, and the New York Age,” stated Vinson. “So even though local papers that might have reported on those things, maybe weren't retained in archives, we have snapshots of Pensacola's Black community, thanks to Walker Thomas reporting on it. And that got printed in newspapers in Indianapolis and New York that have been preserved and are available to search digitally. So if you cast a wide net, you'll probably find some really interesting information.”

The Chronicling America project of the Library of Congress, the National Archives catalog, and Florida Memory are among state and federal collections; UWF LibGuides currently has access to 315 databases, including Ebsco, NewsBank, and ProQuest.

Local physical archives are available at the UWF Historic Trust, Voices of Pensacola Multicultural Center, Second Floor; University Archives and West Florida History Center; UWF Pace Library, Basement; West Florida Public Library Main Branch, Second Floor; and Escambia Clerk of Court Public Records Center. Also, there are city directories Sanborn maps, and aerial photos.

For people with roots in Pensacola, Vinson joined the research team from the West Florida Genealogy Society to create the 1821 Sampler mosaic, which documented all the people known to be living in Pensacola at that time to commemorate the Bicentennial of Florida’s entry into the United States and the 200th Anniversary of Escambia County.

To exercise some of their new skills, workshop participants were invited to join in a case study of Pensacola resident Myrtle Johnson Watson Brown. She was a licensed, trained cosmetologist and public school teacher, who was born in 1916. One-half of the room searched census records for her mother, while the other half looked for her father.

“There he is,” said one workshop goer, upon finding the family in the 1920 census. “Oh, yeah, there he is. That’s so cool,” responded another.

To balance any information found about her family, Reshard invited Brown's granddaughter to help confirm and fill in details.

"So it gives you some context; it's not just this person was a delivery person, but 'Oh, they delivered ice for the Lewis Bear Company,'" Reshard stated as an example.

Sherry Pond was among the participants who came away from the workshop armed with new strategies for jumpstarting their own family research.

“This was very helpful in the sense that it helped me to be aware of what to look for, where I can find information,” said Pond.

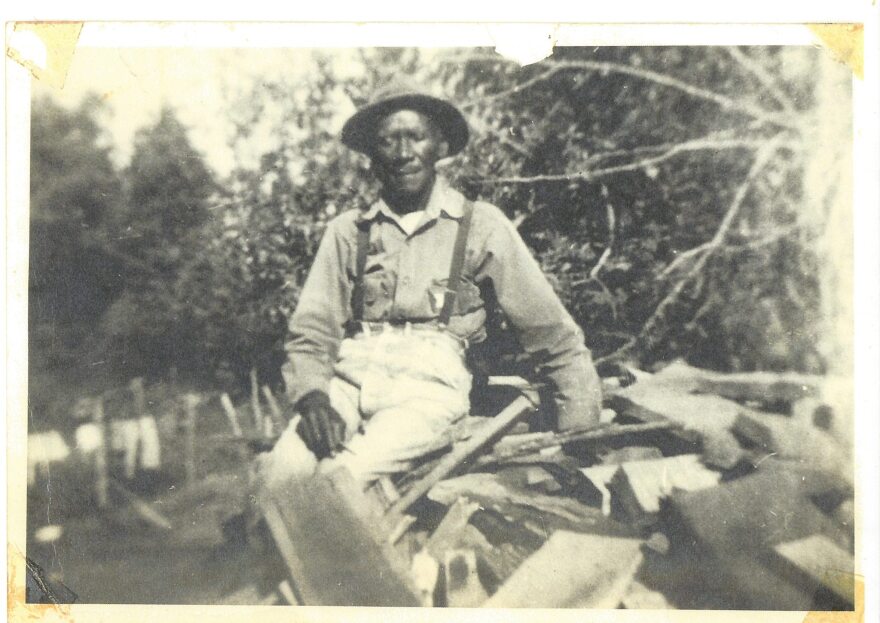

Reshard’s advice is to be curious and keep asking and looking, because as there may be more to be found. As was the case with the discovery of her family’s early 1900s school records in a house about to be torn down, she believes that a rare school yearbook, personal letter, or photo of your ancestor is likely in somebody’s archives.

“I am determined to know that somebody has a photo,” she said. “Somebody has it.”