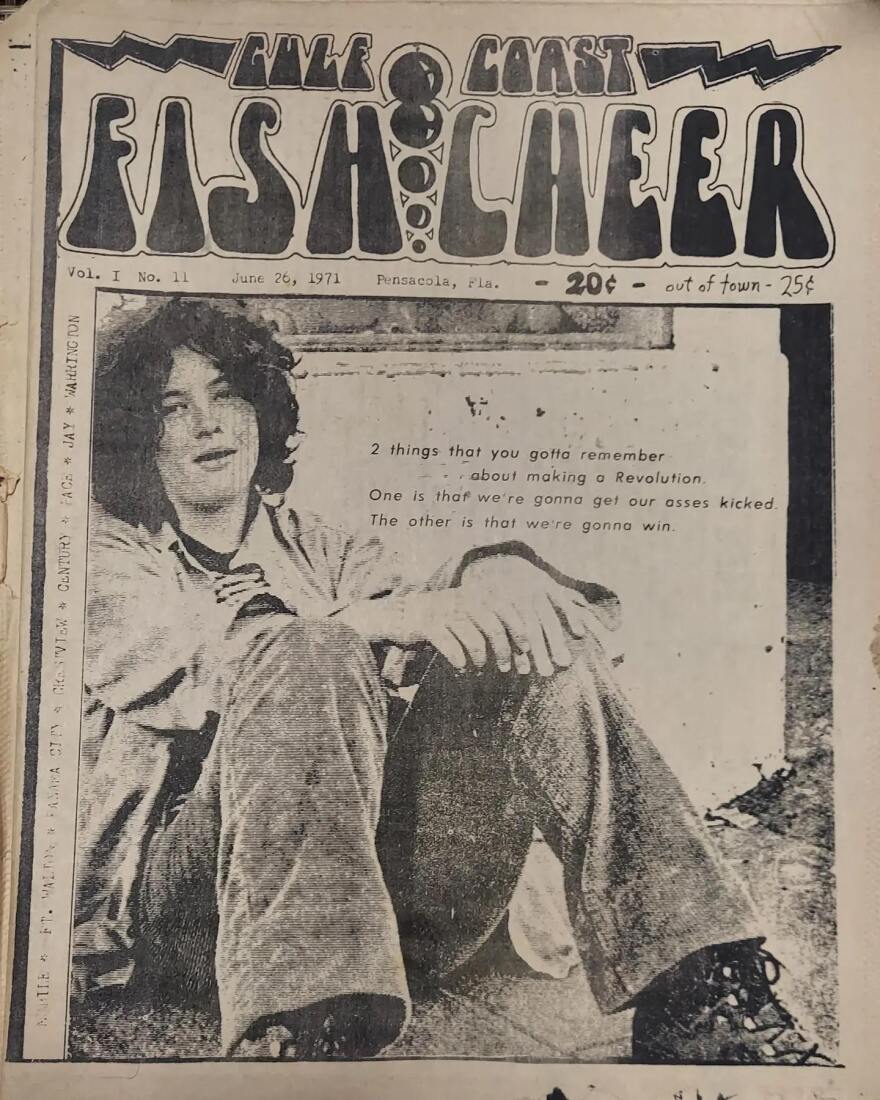

The 309 Punk Project will be hosting “War Against Conformity: Pensacola’s 1970s Underground Press” on Saturday and Sunday. The event and series of discussions will highlight the underground press movement from the 1960s and 1970s, with a focus on Pensacola’s short-lived Gulf Coast Fish Cheer.

“They were speaking out against a larger society that just didn’t understand them,” said Scott Satterwhite, curator of the War Against Conformity exhibit on Sixth Avenue in Pensacola. “This had to deal with things from the local newspaper and how they were often derided in it and different parts of the culture. The underground press, here in Pensacola in particular, was a place where a lot of people didn’t feel like they fit into society, but they knew there were a lot more of them out there. They were trying to connect with other people.”

Gulf Coast Fish Cheer, whose name was derived from the Country Joe and the Fish song “The ‘Fish’ Cheer,” was an underground newspaper that formed in 1970 in Pensacola’s Old East Hill neighborhood. Its writers consisted of UWF and Pensacola Junior College students, Vietnam war veterans, and others involved in the counterculture.

Shying away from the mainstream local newspapers of the time, Fish Cheer touched on subjects that were largely unaddressed and radical at the time. Topics highlighted in the paper included black liberation, the antiwar movement, mental health issues, and others.

“The thing that surprised me the most about the paper when I was looking and going through the issues was the feminist politics of the paper, it’s something that caught me off guard a little bit,” Satterwhite said. “I expected the antiwar stuff and the countercultural things you’d expect in one of these newspapers, but the heavy feminist presence in the paper was tremendous, not only for that time but also in comparison to bigger newspapers from that period where you definitely don’t see it as much.”

By the late 1960s, the underground press movement had exploded, with at least one active paper in most major and minor cities in the United States. This, coupled with the 1970 Kent State massacre, where four college students were killed protesting the Vietnam war, were factors that brought the underground press movement to Pensacola.

“A lot of the 1960s counterculture and underground press, and the hippies involved with these movements, were reacting to not being heard, not being understood, and being misunderstood and misrepresented,” Satterwhite said. “They decided to write the story and they decided to create their own media.”

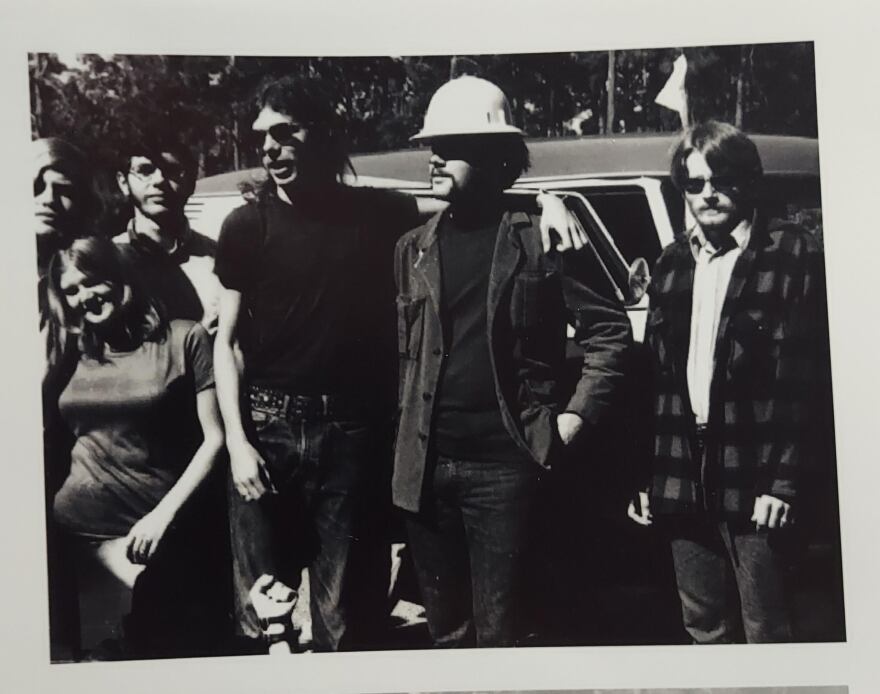

Fish Cheer covered both local and national stories that were not covered by other mainstream papers at the time. This includes rallies in and around Pensacola.

“They were really in touch with what was happening in the community itself, and were a part of the stories they were writing about,” Satterwhite said. “That’s also a hallmark of the underground press called activist journalism, where you’re doing the actions, and then you’re writing about them afterward.”

Both active-duty military personnel and veterans were also contributors to Fish Cheer. To Satterwhite’s surprise, some naval officers from nearby Naval Air Station Pensacola are cited for writing against the Vietnam War in the paper.

“People wrote from the decks of the USS Lexington about their experiences in the military and people wrote about being in the navy brig,” Satterwhite said. “There was organizing within the U.S. military not just from disaffected, angry veterans who just came back from the war, but also from naval officers, which you don’t see very often.”

“They had a group called the Concerned Officers Movement, and they used the newspaper to broadcast to other military officers that there were more of them out there than they might think,” Satterwhite added.

Within a year of Fish Cheer’s founding, the hippie movement began to dissolve, inevitably taking Fish Cheer with it. Even so, this gave rise to a new countercultural movement: the punk movement.

Beginning in the early 1970s as a continuation of and reaction to the hippie movement, the punk movement can be regarded as a “younger brother” to the hippie movement. Still around today, and closely intertwined with the 309 Punk Project, the punks have similar ideals to the hippies, including non-conformity and direct action.

“Punks tend to have a little bit more of a realistic sense of the world, and I think we got that from the disillusionment from the hippies,” Satterwhite said. “A lot of the hippies looked at the world with the peace and love aspect, and punks have that too, but it was also with a healthy dose of ‘yeah, but we also know what the world is like, and we’re not looking at this with rose-colored glasses anymore.’”

As the punk movement began to take form, underground journalism continued. Similar to papers like Fish Cheer, the punks adopted an underground medium known as fanzines.

“What surprised me a lot when I was looking at Fish Cheer is how similar these struggles are,” Satterwhite said. “You can almost literally cut out articles from one of these newspapers and put it into a punk fanzine, and you wouldn’t know the difference as far as the content and discussions that are taking place.”

Satterwhite, who has studied Gulf Coast Fish Cheer for over 20 years, hopes that the War Against Conformity event can help people draw the intergenerational connections between the hippie and punk movements. He also points out that both the former Fish Cheer and current 309 Punk Project headquarters are within four blocks of each other.

“Pensacola has always had a really interesting, often radical, version of the counterculture around,” Satterwhite said. “For as long as you can imagine, Pensacola has had that. It’s always been a part of the story, it’s just never written about.”

The War Against Conformity exhibit will have the only known full-run edition of Gulf Coast Fish Cheer on display. Copies of other underground papers, including Ramparts, Great Speckled Bird, and Black Panther will also be on display.

“Being able to open the newspaper for the first time and see these papers, 50 years old, and read them, they are just as interesting and just as powerful as I’m sure they were for those people when they first saw them,” Satterwhite said.

The War Against Conformity exhibit will be open for viewing from 4 to 7 p.m. Saturday and 2 to 6 p.m. Sunday. A conversation with Gulf Coast Fish Cheer editor Patricia Bint will take place at 7 p.m. Saturday, along with a talk by Aaron Cometbus, “From Fish Cheer to Smell of Dead Fish — the bridge between hippie and punk,” at 6 p.m. Sunday. The exhibit and conversations will take place at the 309 Punk Project, 309 North Sixth Ave., Pensacola.