For Black History Month 2021, we look back at the height of the Civil Rights Movement and the day that became known as “Bloody Sunday 56 years ago.”

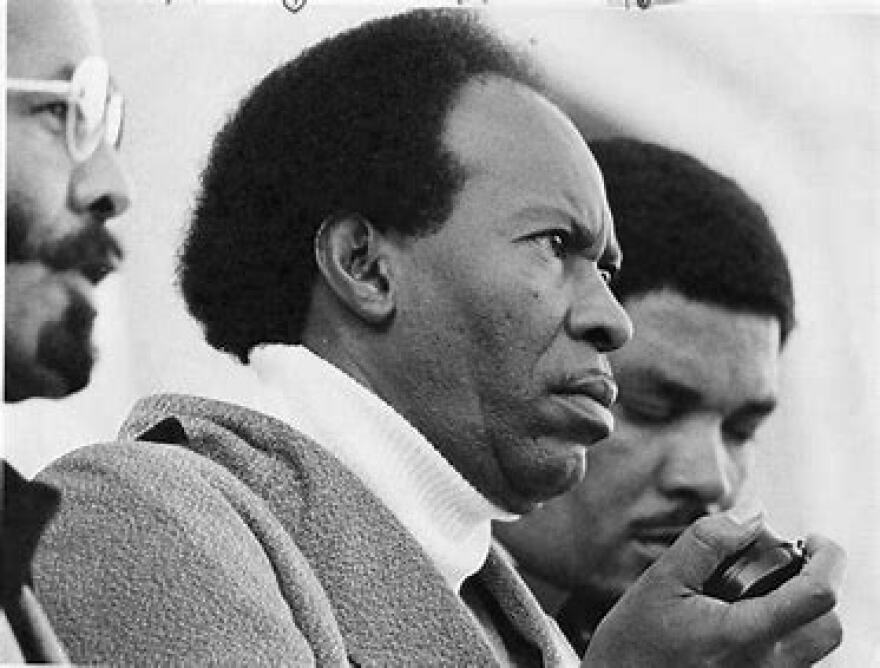

Rev. H.K. Matthews, who just turned 93 years old, was 37 and working as a janitor at a small medical office in Pensacola, when the call went out for participants to march. He put down his mop, climbed into his 1957 pink and white Ford Fairlane, and drove the 175 miles to Selma.

“I was not in a leadership role in Selma,” said Matthews. “But I was there to be in the mix, to show my support, to make myself feel as if I was a part of what was going on at that time.”

On March 7, 1965, 600 people gathered at Brown Chapel AME Church to begin the 54-mile trek from Selma to Montgomery. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. had an engagement in Atlanta, so Hosea Williams and future Congressman John Lewis would lead. After walking through downtown Selma without incident, things changed as they approached the Edmund Pettus Bridge.

Alabama State Troopers, in helmets and gas masks and wielding nightsticks, first stopped the marchers and then advanced into them on foot and on horseback. Lewis and others were seriously injured. Matthews was also among the marchers who were tear-gassed and hurt.

“The most damaging blows were dealt to those who were at the front of the march, but they were just indiscriminately beating people,” Matthews said. “They didn’t ask me whether I was a leader or a follower when they started flailing. I did happen to catch a few blows.”

Thanks to the national media, the story of Bloody Sunday spread from coast to coast. President Lyndon B. Johnson, sensing the mood of the country, addressed Congress on national TV a week later. He asked for a comprehensive voting rights bill; lawmakers acquiesced, and Johnson signed it into law in August, 1965.

“What happened in Selma is part of a far larger movement that reaches into every section and state of America,” the president said. “Their cause must be our cause, too; because it’s not just Negroes, but really it’s all of us who must overcome the crippling legacy of bigotry and injustice. And we shall overcome.”

“People were just horrified, because they just didn’t know that other human beings could treat other human beings the way we were treated on that bridge,” Matthews said.

Matthews was also quick to point out that the march was not exclusive to African-Americans.

“There were white people involved in that march – who already had a right to vote,” said Matthews. “But they were there to support our efforts because they knew that [the] denial of our voting rights was wrong.”

Martin Luther King called for civil rights supporters to come to Selma for a second march. Members of Congress urged him to hold off, until a court could rule if the protesters were entitled to federal protection. King led the second protest on March 9, but turned it around at the Edmund Pettus Bridge.

The third march, on March 21, was successful.

“Under the leadership of Dr. Martin Luther King, and under the presidentially-ordered protection of the National Guard and soldiers of the United States Army, the long-awaited, long-delayed freedom march to Montgomery begins,” intoned the newsreel announcer. “The bridge, where before the marchers had been turned back, is crossed without incident.”

“Let the nation and the world know, we are tired now,” said King. “We are trying to remind the nation of the urgency of the moment. Now is the time.”

Matthews says more challenges remain in the Civil Rights movement. One of them is to make sure current and subsequent generations of Americans are educated about the struggles those pioneers endured.

“We as adults and older people who were involved in the movement, and those who were not involved but who knew of about it,” said Matthews. “The failure lies with us and not our young people. Because we are not teaching what happened. Most of them have no clue, no appreciation of what we went through.”