Florida is moving in the wrong direction on prenatal care and climbing the national rankings for all the wrong reasons.

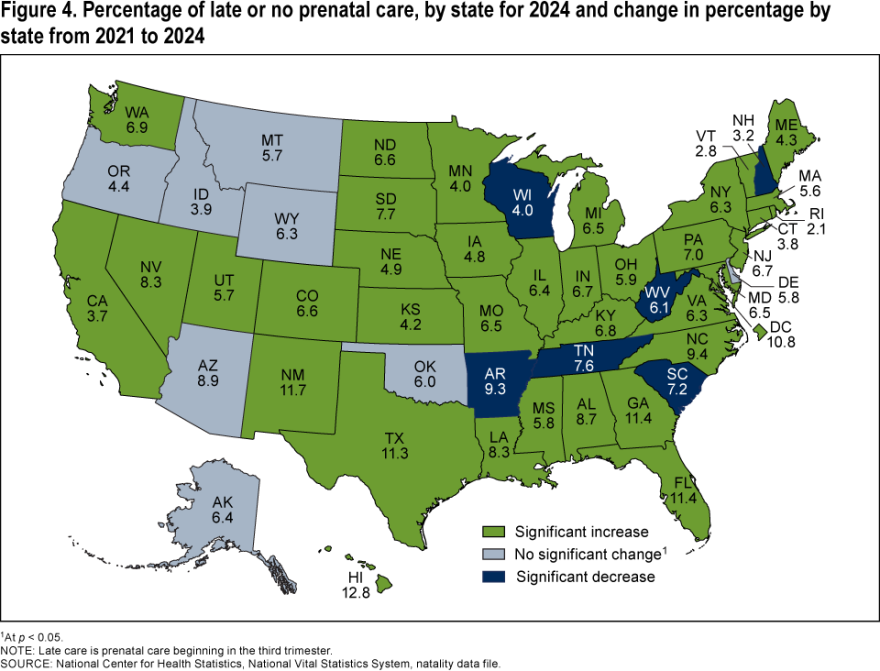

The share of Florida mothers receiving late or no prenatal care jumped 25% between 2021 and 2024, rising to 11.4%, tied with Georgia for the third-highest rate in the country, according to new data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Only Hawaii (12.8%) and New Mexico (11.7%) fared worse.

Nationally, the share of U.S. births in which mothers began care in the first trimester fell from 78.3% in 2021 to 75.5% in 2024, according to the report, which was released Thursday.

Meanwhile, starting care later in pregnancy or getting no care at all has been on the rise. Prenatal care beginning in the second trimester rose from 15.4% to 17.3%, and starting care in the third trimester or getting no care went from 6.3% to 7.3%.

"We know that early engagement in prenatal care is linked to better overall health outcomes," said Dr. Clayton Alfonso, an OB-GYN at Duke University in North Carolina. When patients delay medical care during pregnancy, "we've missed that window to optimize both fetal and maternal care."

Late or no prenatal care increased in 36 states and the District of Columbia over the four-year period. The largest increase was in Utah (54%, from 3.7% to 5.7%), followed by Massachusetts (3.7% to 5.6%) and Rhode Island (1.4% to 2.1%).

Florida was tied for the 10th largest increase after jumping from 9.1% in 2021, when it ranked fifth highest nationally.

The rate decreased in six states: Arkansas, New Hampshire, South Carolina, Tennessee, West Virginia, and Wisconsin. The changes in eight states were not significant.

While the overall trend identified in the report held for nearly all racial and ethnic groups, the decrease in early prenatal care was higher for moms in minority groups. For example, first-trimester care dropped from 69.7% in 2021 to 65.1% in 2024 for Black mothers.

Getting late or no prenatal care raises the risk of maternal mortality, which is much higher among Black mothers.

Michelle Osterman, lead author of the report, said the overall findings represent a shift. Between 2016 and 2021, the timing of when U.S. women started prenatal care had been improving.

The earlier prenatal visits begin, doctors said, the earlier problems can be caught. Visits give doctors a chance to share health guidance, and can include blood pressure checks, screenings, blood tests, physical exams and ultrasound scans.

The report doesn't provide reasons why prenatal care is starting later. But the proliferation of maternity care deserts across the nation is a growing concern, said Dr. Grace Ferguson, an OB-GYN in Pittsburgh.

Many hospitals have shut down labor and delivery units "and the prenatal care providers that work at those hospitals also have probably moved," said Ferguson, who was not involved with the report.

Alfonso, who was not involved in the CDC report, said he also suspects that access issues are pushing prenatal care later, particularly in rural areas. Patients may have to travel farther to get to appointments and may struggle to find a practice that accepts their insurance, particularly if they have Medicaid.

A 2024 March of Dimes report found that more than 35% of U.S. counties are maternity care deserts, meaning there's no birthing facility or obstetric provider. Women living in these areas receive less prenatal care, the report showed.

The report says about 19% of Florida counties are considered maternity care deserts, lacking hospitals or birth centers with obstetric care. Roughly 10.8% of Florida women live more than 30 minutes from a birthing hospital, and 20.8% receive inadequate prenatal care, exceeding national averages.

Health care advocates say Florida's issues also include delays in Medicaid enrollment that can push women further into pregnancy before they see a doctor.

In recent years, Florida lawmakers extended Medicaid postpartum coverage for new mothers from 60 days to 12 months. But the state has not adopted full Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act, a policy supporters argue would broaden access to health coverage before and during pregnancy.

All 50 states are receiving funding over the next five years from the $50 billion federal Rural Health Transformation Program, part of the "Big Beautiful Bill" spending package passed last summer. Florida's share will be nearly $210 million.

Florida officials say those dollars will be used to expand primary care access and recruit providers in the state's 31 rural counties. The investments are aimed at strengthening rural health infrastructure — a key factor in delayed prenatal care in some counties.

Even with that infusion, doctors fear that things could get worse.

"If this trend continues," Alfonso said, "I worry about kind of what that would mean for morbidity and mortality for our moms.

Information from the Associated Press was used in this report.

Copyright 2026 WUSF 89.7