The population of Florida panthers has increased tenfold over the past 30 years, thanks to the introduction of pumas from Texas into the Everglades.

Despite that outside DNA, new research finds panthers have kept their genetic diversity.

As their numbers rebounded, some researchers feared their genetics would be replaced by their Texas cousins. A new study from UCLA shows they retained their genetic diversity, meaning they're still considered a distinct species.

Scientists had little choice back in 1995 if they wanted to save the species, which had dwindled to around 20 animals clustered around the Big Cypress Swamp in Southwest Florida.

ALSO READ: Easement purchase protects 1,003 acres of prime panther habitat on a Highlands County ranch

Kirk Lohmuller is a professor of ecology and biology at UCLA and one of the authors of the new study, which was published Monday in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

"We found that the genetic diversity in the Florida panther after the translocation from Texas went up," he said, "and that could potentially be a positive thing for the survival of the species."

Lohmuller said this could be used as an example to be replicated for other isolated species.

"Some people even call them like a textbook example of genetic rescue, because I think they were one of the first attempts in natural populations to do that," he said, "And I feel like they definitely been used to try to do it in other species."

The study shows that inbreeding among the species was minimized thanks to the new diversity of genes.

Diana Aguilar Gomez is a geneticist at UCLA and the study's principal author. She says the inbreeding happening before pumas arrived — characterized by misshapen tales and trouble reproducing — has largely been eliminated.

"You always have two copies of your genes, one from your mother and one from your father," Gomez said. "Let's say one copy is bad, has some defect, but then the other copy, it kind of compensates for it. So that's what's happening in the Florida panthers. They still have, like these mutations that are harmful, but then they have the other copy that's kind of compensating."

She says that means the species has a greater chance for long-term survival.

"One concern with this sort of translocation is that if the individuals you bring in themselves carry a set of deleterious mutations, and if some of them are particularly strongly deleterious or really bad, then if once that new ancestry comes in, it could actually increase the amount of deleterious mutations," she said of the new blood.

"And if the population remains small and continues to have mating among close relatives, those new deleterious mutations might become expressed and leading to a reduction in fitness," Aguilar Gomez continued. "So in some sense, it's a bit lucky what happened in Florida with in terms of not bringing in more strongly deleterious mutations. And so, therefore, the genetic rescue worked."

Overall, the study found:

- Local ancestry and genetic diversity have not been replaced by the introduced individuals from Texas

- The total harmful mutations was not reduced by the genetic rescue, but the ones in the homozygous state, meaning they had two copies of the gene, decreased.

- Increased heterozygosity, or mixed copies of genes, increased, which increases fitness.

- The findings highlight the success of the genetic rescue, but also that its effects might be transient and that continued management of the panthers is needed.

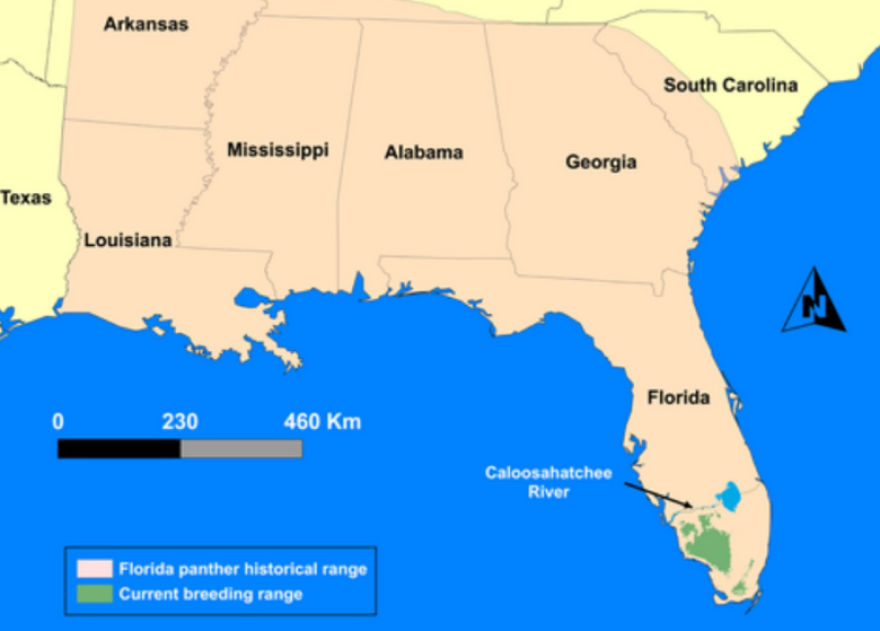

The panther's historic territory used to be the entire Southeast. But they were hunted so relentlessly that by the 1970s, only a handful were left in the swamps west of the Everglades.

Their long road to recovery began in Fisheating Creek, north of the Caloosahatchee River. In 1972, a cougar hunter from Texas tracked down one underfed female panther, and it was discovered that inbreeding was hampering their ability to reproduce. Twenty-three years later, state legislators supported a plan for him to bring in eight female pumas from West Texas.

Nature has since taken its course. As many as 230 panthers now roam the state, mostly in the Big Cypress region of Southwest Florida.

Most of the panthers live in Southwest Florida, below the Caloosahatchee River. In 2021, a female panther was spotted near Fisheating Creek for the first time in 43 years.

In 2022, a panther was killed on a roadway in southeast Hillsborough County for the first time since 2003.

In July, a 2- to 3-year-old male was killed trying to cross busy Interstate 75 in Pasco County.

It was the 10th death of a Florida panther so far this year — and the only one discovered north of their primary habitat in Collier, Lee and Hendry counties. Last year, 36 of the endangered species were killed — with only 13 deaths reported in 2023.

Copyright 2025 WUSF 89.7