Why is plastic a problem? The obvious answer is that we produce a lot of it and it's everywhere, even in places we don't expect to find it, like chewing gum or tea bags. It's also made out of dirty, polluting fossil fuels and is modified with dangerous chemical additives. Every step in the manufacture, use, and disposal comes with both environmental and health risks.

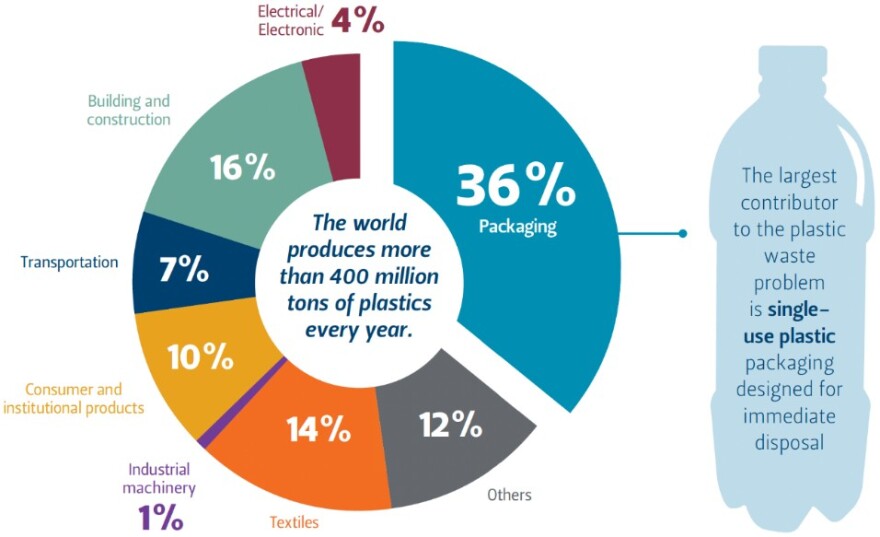

I'm not saying that plastic is not essential for many uses, but fully 34% of manufactured plastic is used in packaging, which is designed for one use and immediate disposal. This so-called single-use plastic can and should be replaced.

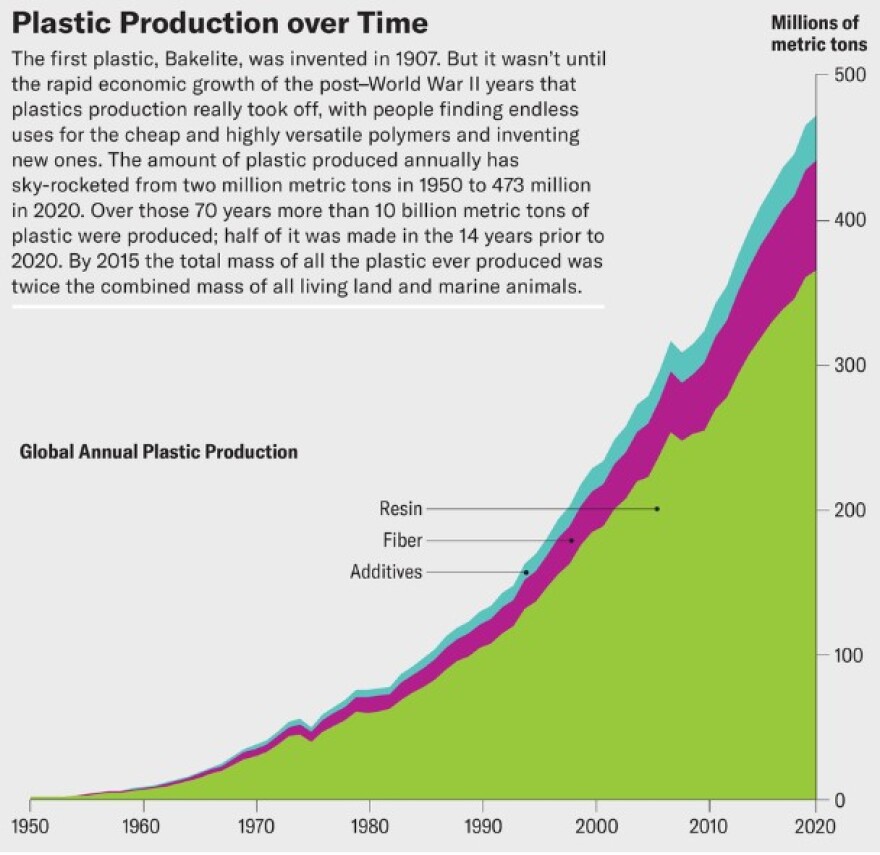

Plastic is thought to be one of humankind's success stories. It's a material that's easy and cheap to manufacture and has almost unlimited uses. Because of that, global plastic production has increased exponentially from 2 million tons in 1950, when it started to be mass produced, to more than 460 million tons in 2019, the last year with published data. In fact, the World Economic Forum predicts a 3.5 to 3.8% growth in plastic production per year through 2050. As striking as these numbers are, they do not include synthetic fibers used in clothing, rope, and other products, which accounted for 61 million tons in 2016.

Unfortunately, plastic can only be considered cheap since its true costs are not really considered. Plastic incurs massive invisible costs to human health and the environment, often referred to as externalities. The 2023 Minderoo Monaco Commission on Plastics and Human Health study calculated that in 2015 alone, the health-related costs resulting from plastic products exceeded $250 billion globally, while the estimated costs from the release of greenhouse gas emissions from plastic production were $341 billion.

Along with plastic production, the use and disposal of plastic can also cause significant environmental and health damage. For example, polyvinyl chloride PVC releases harmful chemicals throughout its life cycle. Manufacturing amidst carcinogens like vinyl chloride use can leach toxic additives like phthalates, and disposal through landfilling or incineration. Plastic releases dioxins, heavy metals, and hydrogen chloride, posing risks from cancer to respiratory damage, with processes like incineration being major sources of persistent pollutants. Leaks and spills from production and transport are also significant hazards. And to make matters worse, plastic hangs around virtually forever. Most of the 8 billion tons of plastic that have ever been manufactured are still around.

And then there's the growing problem of microplastics. These will all be discussed in future podcasts.

So first, production of plastic requires four steps:

- getting the raw materials

- synthesizing the polymers

- compounding the polymers into a usable product

- molding or shaping the plastic

All of which are polluting and use dangerous chemicals, which contribute to global emissions associated with air and water pollution as oil spills, leading to toxic contaminations.

Most plastics start from fossil fuels like oil or natural gas. I'll be discussing bioplastics a bit later. Eight to 10% of the annual petroleum consumption in the US and worldwide is used to make plastics. Of that, 12 million barrels of petroleum are used in the U.S. just to make plastic bags. Extraction of fossil fuels is a dirty business. It uses dangerous chemicals and leaves behind toxic waste and air pollution. We all remember the Deepwater Horizon spill and the environmental damage that it caused. Well, the fossil fuel industry has hundreds of mini deepwater horizons every year. We just don't hear about them. We also don't hear about the toxic waste stumps in the ocean, in lagoons, or in waterways. Then there's fracking, which has been implicated in both environmental and health damage. Just digging into the earth to extract these materials damages the soil and land and makes the area more susceptible to natural disasters like mudslides, earthquakes, and flash floods. Extraction companies often dump the rock and soil dug up into nearby waterways and ravines, interrupting water flow and disturbing ecosystems.

As 99% of plastics are created from chemicals of fossil origin, plastic production is closely linked to the petroleum industry. The rapid global growth of the plastic industry is largely fueled by the availability of cheap shale gas and growing investments from the fossil fuel industries. Indeed, petrochemicals are expected to be the largest driver of global oil demand growth from now through 2040, outpacing their use in the transportation industry, in power production, or in buildings. The strong linkages between plastics and fossil fuels also mean that plastic production is one large driver of climate change.

In fact, according to the EPA, it is estimated that in 2019, plastic products were responsible for 3.4% of global greenhouse gas emissions through their life cycles, with 90% of these emissions coming from the production and conversion of fossil fuels into new plastic products. It further reports that unless human behavior changes, greenhouse gas emissions associated with the life cycle of plastic products are expected to double by 2060. The World Economic Forum projects that without intervention, the global plastics industry will account for 20% of total oil consumption and up to 15% of global carbon emissions by 2050.

But that's only extraction. After that, there's refining and cracking. Refining plants process fossil fuels to obtain ethane and propane. These are further broken down by cracking into ethylene and propylene. According to the EPA, refineries are among the most toxic industries in this country, with their pollutants causing cancer, pulmonary and heart diseases, neurological, reproductive, and developmental diseases, both to employees and the surrounding communities. They are also often located near urban areas and particularly near disadvantaged communities.

Next is the processing, where chemicals are added to plastic during its production to give the produced resin certain properties, such as malleability or rigidity. An independent report published in 2023 found that up to 13,000 chemicals are used in plastic production. Out of these, 3,200 are verified to be chemicals of potential concern, but the figure could be bigger, considering that hazard data is missing for 6,000 of them. Moreover, only 1% of chemicals of concern used in plastics are regulated.

Some of these chemicals are known endocrine disruptors and have been linked to birth defects, diseases, including cancer, autoimmune diseases, infertility, and cognitive and behavioral disorders. For example, one of the most well-known of these chemicals, bisphenol A, is found in polycarbonate plastics and epoxy resins. Exposure to BPA is a concern because of the possible health effects on the brain and prostate gland of fetuses, infants, and children. It can also affect children's behavior. Additional research suggests a possible link between BPA and increased blood pressure, type 2 diabetes, liver failure, cardiovascular disease, and neurological issues. In numerous studies, more than 90% of people tested worldwide had BPA in their bodies.

I'll be discussing the evidence that using materials containing BPA can leach the chemicals into our food and bodies in the next podcast, but plastics such as polycarbonates are often used in containers that store food and beverages, such as water bottles.

Epoxy resins are often used to coat the inside of metal products such as food cans, bottle tops, and water supply lines. Some dental sealants and composites may also contain BPA.

There are petroleum-based alternatives to BPA, such as bisphenols, af, F, S, and Z, which are structurally similar to BPA and, according to scientists, are no safer and may pose similar environmental and health risks. BPA-free doesn't mean chemical-free or safe.

In the last few years, there have been a number of papers discussing plant-based alternatives to BPA, such as bisguaiacols and bissyringols, which appear to have lower estrogenic activity and developmental toxicity. More research needs to be done to determine if they're safe, but we do know that the current additives are not.

Other plastic additives are phthalates, which are used to make plastics more flexible, and have been linked to brain development problems in children.

Only by using materials like glass or stainless steel can you be assured that you're not getting those endocrine disruptors and developmental toxins.

In addition to the almost half a billion tons of plastic already discussed, there are the almost 61 million tons of synthetic fibers such as polyester and nylon, which are used in clothing, furniture, upholstery, and other household goods such as carpets and curtains.

Currently, synthetic fibers constitute almost two-thirds of all textile fibers produced globally, dominated by polyester. Processes used to convert raw polymers to finished fiber-based products, such as dyeing, impregnating, coating, and plasticizing, involve multiple hazardous chemicals.

Some dyes used in synthetic fibers are highly carcinogenic as well as genotoxic, and allergenic. One class of dyes, aromatic amines, was among the first synthetic chemicals to be produced and was documented as early as 1895 to cause cancer of the bladder. Other dyes can cause allergic reactions and skin irritations. Some dyes found in clothing with printed graphics, including socks and infant clothing, are dermal sensitizers, genotoxic, and can act as endocrine disruptors. Synthetic textiles with PVC prints, which contain high levels of phthalates, are common, especially in children's clothing and other infant products such as nylon sheets, cot mattresses, and diaper changing mats.

In addition to dyes, a number of metal(loids)s are found in some synthetic fabrics, including high concentrations of chromium, copper, and aluminum in polyester, and high concentrations of nickel and iron in nylon. Concentrations of these metals, such as chromium, lead, and nickel, have been found to exceed recommended limits in some clothing samples tested.

Lastly, some synthetic textiles are treated with formaldehyde-releasing compounds and resins to prevent creasing. Formaldehyde, a known carcinogen, has been detected in clothing Items at concentrations 40 times higher than specified by International Textile Regulations. Some synthetic textiles are treated with metal nanoparticles, which act as antimicrobial silver or UV absorption titanium agents. However, product disclosure is largely lacking, and the forms and concentrations in which these metals are present are unknown. Nevertheless, dermal exposure is hypothesized to be a likely exposure route, which I'll discuss in the next podcast.

So what about bioplastics? Bioplastics are defined as plastics made wholly or in part from renewable biomass sources such as sugar cane, corn, vegetable oils, yeast, and vegetative waste, and may or may not be biodegradable or compostable. There are many classes of bioplastics depending on the source material. However, these plastics can contain petroleum-based materials or use petroleum based material or metals in their polymerization, so the definition can be murky. Only one of the 10 most common bioplastic types, PHAs are the only bioplastic that is 100% bio based, marine, and soil biodegradable, which can be done in a home composting container as well as biologically produced. They are synthesized via microbial fermentation of renewable feedstocks like sugars or fatty acids, making them "biologically produced" rather than just chemically synthesized by bioderived ingredients.

Although the source of the polymers may be better for the environment, the processing to get usable plastic from most of them may not be. One process uses hydrochloric acid and sodium hydroxide, leaving large amounts of hazardous solvents. Also, many bioplastics are not biodegradable at all, or without extensive processing or industrial composting facilities, and up to 10% of the material can remain and still be defined as biodegradable.

I'll go into the details of the ecotoxicity of bioplastic disposal when I discuss plastic disposal in a later podcast. The next podcast will discuss plastic use. If there's a topic you've heard on the Ecominute that you'd like me to examine in more detail, or an environmental issue that you'd like to learn more about, email me at ecominute@wuwf.org.