You may have come across a meme showing an ancient fish known as Tiktaalik.

It shows the green, eel-like creature crawling out of the sea about 375 million years ago — about the time that scientists say fish developed the physical characteristics to survive on land — only to be directed to turn around.

The joke, as far as the meme goes, is that the fish should crawl straight back into the water to avoid the woes of our modern times.

Now, a new study published in Nature suggests a relative of Tiktaalik – named Qikiqtania wakei – did just that.

Dunno who made this, but yes. pic.twitter.com/JhxAACkTDu

— Matthew Cobb (@matthewcobb) December 7, 2021

"You had this evolutionary series of fish evolving to walk, but this one said, 'Eh, not going to do that one. I'm going back in,'" said Neil Shubin, a paleontologist at the University of Chicago who co-authored the study.

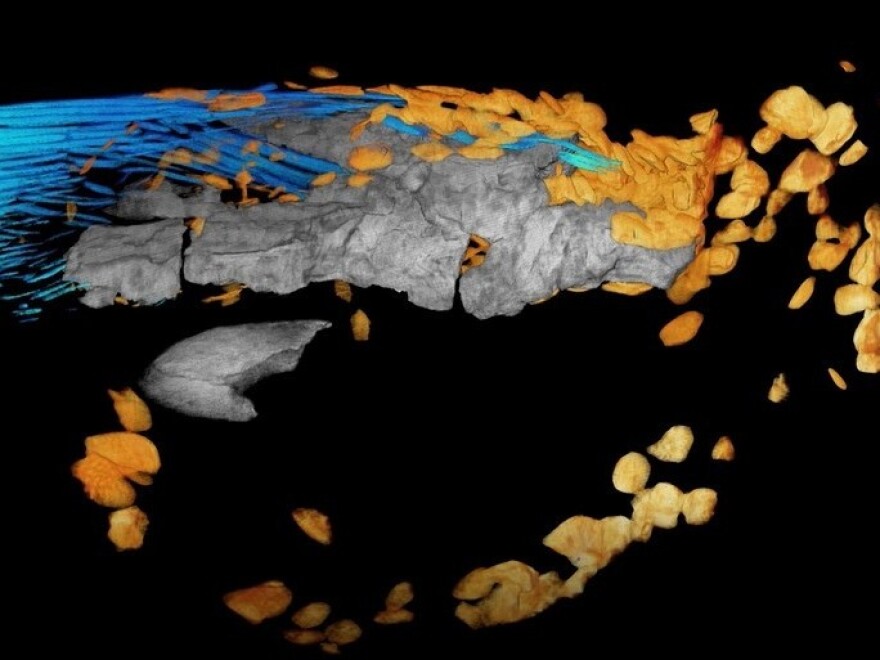

Shubin was part of the team who discovered Tiktaalik during a 2004 expedition in the Canadian Arctic. Qikiqtania was found on the same trip, but the fossil went mostly unstudied while the team focused on Tiktaalik.

"This new species is a very close cousin of Tiktaalik. We know that by looking at all the features," Shubin said. "In fact, it's a very close cousin of both Tiktaalik and creatures with arms and legs and fingers and toes, so-called tetrapods."

Early tetrapods were likely spending more and more time out of the water during this period, Shubin said. The arrangement of bones and joints in these animals' fins was starting to resemble arms and legs, which would have allowed animals like Tiktaalik to prop themselves up in shallow water and survive on mudflats.

But Tom Stewart, an evolutionary biologist at Penn State who also worked on the study, said Qikiqtania's physiology suggested it was swimming in open water. Qikiqtania's fins are the result of its swimming ancestors crawling onto land, then returning to the water.

"That's an unexpected pattern," he said. "That's not something that would have been predicted before we had a fossil like this."

The study expands paleontologists' understanding of this period in evolutionary history by showing that animals weren't just evolving from water-based fish to land-based tetrapods.

"The transition from life in water to life on land was going both ways," Shubin said.

Qikiqtania is a vivid counterexample to the long-debunked, yet enduring myth that evolution is a linear progression from one species to the next.

"We get introduced to the idea of evolution through images like an ape that slowly stands upright and then produces a man walking," Stewart said. "Those are some of these classic, iconic teaching tools ... but really, evolution doesn't work in that way."

Shubin said evolution was more accurately described as a set of branching paths, rather than a ladder. "Evolution is much more of a bush," Shubin said, "a tree of creatures evolving in many different directions."

We'll see how the memes evolve from here.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.